Research: publications

Blocking mobile internet on smartphones improves sustained attention, mental health, and subjective well-being

w/ Noah Castelo, Kostadin Kushlev, Mike Esterman and Peter Reiner

PNAS Nexus (2025)

View Article Online

Smartphones enable people to access the online world from anywhere at any time. Despite the benefits of this technology, there is growing concern that smartphone use could adversely impact cognitive functioning and mental health. Correlational and anecdotal evidence suggests that these concerns may be well-founded, but causal evidence remains scarce. We conducted a month-long randomized controlled trial to investigate how removing constant access to the internet through smartphones might impact psychological functioning. We used a mobile phone application to block all mobile internet access from participants’ smartphones for 2 weeks and objectively track compliance. This intervention specifically targeted the feature that makes smartphones “smart” (mobile internet) while allowing participants to maintain mobile connection (through texts and calls) and nonmobile access to the internet (e.g. through desktop computers). The intervention improved mental health, subjective well-being, and objectively measured ability to sustain attention; 91% of participants improved on at least one of these outcomes. Mediation analyses suggest that these improvements can be partially explained by the intervention's impact on how people spent their time; when people did not have access to mobile internet, they spent more time socializing in person, exercising, and being in nature. These results provide causal evidence that blocking mobile internet can improve important psychological outcomes, and suggest that maintaining the status quo of constant connection to the internet may be detrimental to time use, cognitive functioning, and well-being.

Mind or machine? Conversational internet search moderates search-induced cognitive overconfidence

w/ Kristy Hamilton and Mike Yao

Journal of Media Psychology (2025)

View Article Online

Searching for and accessing online information through search engines causes digital media users to become overconfident in their own knowledge—in a sense, to attribute online knowledge to themselves. If searching the internet via search engine leads people to conflate digital information as self-produced, what happens when features of our devices turn information search into an interpersonal situation? The proliferation of anthropomorphic technology underpinned by artificial intelligence (AI) may challenge the current view of search-induced cognitive overconfidence. In two experiments, we investigate how using digital agents to search for information moderates the misattribution of online information to one’s own memory. We find that, in contrast to using a search engine, using a digital agent to access online information does not lead to higher estimations of cognitive self-esteem (Experiment 1). Moreover, using a humanized digital agent may lead to lower cognitive self-esteem than using a non-humanized digital agent or thinking alone (Experiment 2). Whereas internet searches can make people overconfident in their cognitive abilities, accessing information through a conversational digital agent appears to clarify boundaries between internal and external knowledge.

Fairness revisionism: Reducing discrimination for the future reduces perceived unfairness in the past

w/ Tito Grillo and Shuhan Yang

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (2024)

View Article Online

Marginalized groups may face systemic discrimination for generations until concrete advancements in society finally ensure fairer treatment for their members. Although fairness advancements may benefit these groups in the present and future, they do not change the past; they cannot undo the discrimination already experienced by previous generations. However, five studies (N = 1672) suggest that fairness advancements that benefit a marginalized group may change how its members perceive their own prior experiences with discrimination, leading them to see these experiences as having been fairer compared to when there are no such advancements. We find evidence of this revisionism of unfair past experiences in different historically marginalized groups (women and immigrants) and cultural contexts (U.S., U.K., and China). Critically, fairness revisionism arises even when fairness advancements have no objective impact on individuals themselves, as long as there are benefits for current and future members of their social group. Fairness revisionism does not arise, however, in response to gains for marginalized groups to which one does not belong, nor when individuals assess fairness in other groups' past experiences from an outsider's perspective. Overall, this phenomenon may be a double-edged sword: it may provide peace of mind for those treated unfairly by assuaging the memory of adverse experiences, but may also make discrimination issues in society seem less pressing based on the perspective of victims themselves.

I share, therefore I know? Sharing online content—even without reading it—inflates subjective knowledge

w/ Frank Zheng and Susan Broniarczyk

Journal of Consumer Psychology (2023)

View Article Online

Billions of people across the globe use social media to acquire and share information. A large and growing body of research examines how consuming online content affects what people know. The present research investigates a complementary, yet previously unstudied question: how might sharing online content affect what people think they know? Sharing signals expertise, and people frequently internalize their public behavior into their private self-concepts. We therefore posit that sharing information on social media may cause people to believe they are as knowledgeable as their posts make them appear. We examine this possibility in the context of “sharing without reading,” a phenomenon that allows us to isolate the effect of sharing on subjective knowledge from any influence of reading or objective knowledge. Six studies provide correlational (study 1) and causal (studies 2, 2a) evidence that sharing—even without reading—increases subjective knowledge, and test the internalization mechanism by varying the degree to which sharing publicly commits the sharer to an expert identity (studies 3-5). A seventh study investigates potential consequences of sharing-inflated subjective knowledge on downstream behavior in the domain of financial decision-making.

Making molehills out of mountains: Removing moral meaning from prior immoral actions

w/ Chelsea Helion, Ian O'Shea and David Pizarro

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making (2022)

View Article Online

At some point in their lives, most people have told a lie, intentionally hurt someone else, or acted selfishly at the expense of another. Despite knowledge of their moral failings, individuals are often able to maintain the belief that they are moral people. This research explores one mechanism by which this paradoxical process occurs: the tendency to represent one's past immoral behaviors in concrete or mechanistic terms, thus stripping the action of its moral implications. Across five studies, we document this basic pattern and provide evidence that this process impacts evaluations of an act's moral wrongness. We further demonstrate an extension of this effect, such that when an apology describes an immoral behavior using mechanistic terms, it is viewed as less sincere and less forgivable, likely because including low-level or concrete language in an apology fails to communicate the belief that one's actions were morally wrong..

People Mistake the Internet's Knowledge for their Own

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2021)

View Article Online

People frequently search the Internet for information. Eight experiments (n = 1,917) provide evidence that when people “Google” for online information, they fail to accurately distinguish between knowledge stored internally—in their own memories—and knowledge stored externally—on the Internet. Relative to those using only their own knowledge, people who use Google to answer general knowledge questions are not only more confident in their ability to access external information; they are also more confident in their own ability to think and remember. Moreover, those who use Google predict that they will know more in the future without the help of the Internet, an erroneous belief that both indicates misattribution of prior knowledge and highlights a practically important consequence of this misattribution: overconfidence when the Internet is no longer available. Thinking with Google may cause people to mistake the Internet’s knowledge for their own.

Conservatism Predicts Aversion to Consequential Artificial Intelligence

w/ Noah Castelo

PLOS One (2021)

View Article Online

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to revolutionize society by automating tasks as diverse as driving cars, diagnosing diseases, and providing legal advice. The degree to which AI can improve outcomes in these and other domains depends on how comfortable people are trusting AI for these tasks, which in turn depends on lay perceptions of AI. The present research examines how these critical lay perceptions may vary as a function of conservatism. Using five survey experiments, we find that political conservatism is associated with low comfort with and trust in AI—i.e., with AI aversion. This relationship between conservatism and AI aversion is explained by the link between conservatism and risk perception; more conservative individuals perceive AI as being riskier and are therefore more averse to its adoption. Finally, we test whether a moral reframing intervention can reduce AI aversion among conservatives.

Consumers as Naive Physicists: How Visual Entropy Cues Shift Temporal Focus and Influence Product Evaluations

w/ Gunes Biliciler and Raj Raghunathan

Journal of Consumer Research (2021)

View Article Online

Marketers often use images to promote their products. For example, an advertisement for kitchen tools might display the tools alongside various ingredients, or an advertisement for a bookstore might showcase pictures of the store’s interior. One underlying visual characteristic of such images is the degree of “entropy”—or disorder—in their content. Motivated by a fundamental principle from physics—namely, that entropy can only increase over time—the present research examines how entropy influences consumers’ judgments and decisions. Across two pilot studies and five experiments, we find that while high-entropy images shift consumers’ temporal focus to the past, low-entropy images shift their temporal focus to the future. These entropy-induced shifts in temporal focus influence consumers’ decisions. Specifically, consistent with the notion of “fit fluency,” we find that consumers evaluate past-related (e.g., vintage) products more favorably when they are accompanied by high-entropy images, and future-related (e.g., futuristic) products more favorably when they are accompanied by low-entropy images. We discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of our findings.

How childhood adversity shapes susceptibility to COVID-19 scams

w/ Tito L.H. Grillo

Journal of the Association for Consumer Research (2020)

View Article Online

COVID-19 scams promise to alleviate the physical and financial risks associated with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, but in fact expose consumers to additional risk. The present research examines how one prominent and unequally distributed socioeconomic factor—resource availability during childhood—influences susceptibility to COVID-19 scams among U.S. adults. One pilot and five pre-registered studies (total N = 1595) provide evidence that childhood adversity may often confer a protective advantage; when environmental threat is low, adults raised in scarcity are less susceptible to scams than those raised in abundance. However, heightened environmental threat—such as evidence of a worsening global pandemic—holds different consequences for those with different socioeconomic backgrounds: whereas adults raised in abundance become less susceptible to scams when the world seems more threatening, adults raised in scarcity become more susceptible to scams under these conditions.

Technology-Augmented Choice: How Digital Innovations Are Transforming Consumer Decision Processes

w/ Shiri Melumad, Rhonda Hadi, and Christian Hildebrand

Customer Needs and Solutions (2020)

View Article Online

This paper provides an overview of recent research that explores how digital technologies such as mobile devices, wearables, voice technology, and recommendation agents are transforming consumer decision-making. We advance a conceptual model of technology-augmented choice that describes how the three Ms of technology—mediums (i.e., device types), modalities (i.e., interaction interfaces), and modifiers (i.e., intelligent agents)—are becoming increasingly integral elements of consumer decision processes. For instance, today’s new technologies often help curate consideration sets, shape how options are evaluated, and even guide choices themselves. As a result, market choices must now be viewed as a joint function of both consumer preferences and the characteristics of the technological environment in which those preferences are expressed. We review examples of empirical research that characterize the interdependencies between technology and decision-making, including how smartphones transform user-generated content, voice technology affects consumer search, haptic interfaces shape product preferences, and search engines alter confidence in choice.

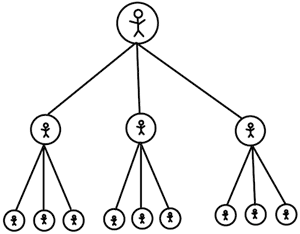

On a "need-to-know" basis: How the distribution of responsibility between couples shapes financial literacy and financial outcomes

w/ John G. Lynch, Jr.

Journal of Consumer Research (2018)

View Article Online

Many people suffer from low levels of financial literacy. Educational interventions intended to increase financial know-how are typically unsuccessful. Why? In this research, we argue that people generally develop expertise on a “need to know” basis; they pay attention to what they think they need to know, when they think they need to know it. We further argue that the distribution of responsibility between relationship partners shapes what each individual believes s/he needs to know. Thus, many people may be ignorant about money because they think they have it covered; not because they know about money, but because they believe they don’t need to know about money. In this research, we explore how relationships shape the development of individual financial expertise. We show that increases in relationship length predict increases in financial literacy for those with high levels of financial responsibility ("household CFOs"), but not for those with low levels of financial responsibility (non-CFOs). These diverging trajectories of financial literacy, in turn, predict differences between household CFOs and non-CFOs in the ability to independently navigate the financial domain.

Media usage diminishes memory for experiences

w/ Diana I. Tamir, Emma M. Templeton, and Jamil Zaki

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (2018)

View Article Online

Download PDF

People increasingly use social media to record and share their experiences, but it is unclear whether or how social media use changes those experiences. Here we present both naturalistic and controlled studies in which participants engage in an experience while using media to record or share their experiences with others, or not engaging with media. We collected objective measures of participants' experiences (scores on a surprise memory test) as well as subjective measures of participants' experiences (self-reports about their engagement and enjoyment). Across three studies, participants without media consistently remembered their experience more precisely than participants who used media. We did not find conclusive evidence that media use impacted subjective measures of experience. Together, these findings suggest that using media may prevent people from remembering the very events they are attempting to preserve.

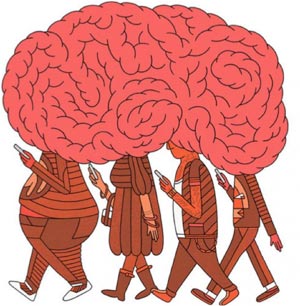

Brain drain: The mere presence of one's own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity

w/ Kristen Duke, Ayelet Gneezy, and Maarten W. Bos

Journal of the Association for Consumer Research (2017)

View Article Online

Download PDF of Article

Download PDF of Web Appendix

Our smartphones enable—and encourage—constant connection to information, entertainment, and each other. They put the world at our fingertips, and rarely leave our sides. Although these devices have immense potential to improve welfare, their persistent presence may come at a cognitive cost. In this research, we test the “brain drain” hypothesis that the mere presence of one’s own smartphone may occupy limited-capacity cognitive resources, thereby leaving fewer resources available for other tasks and undercutting cognitive performance. Results from two experiments indicate that even when people are successful at maintaining sustained attention—as when avoiding the temptation to check their phones—the mere presence of these devices reduces available cognitive capacity. Moreover, these cognitive costs are highest for those highest in smartphone dependence. We conclude by discussing the practical implications of this smartphone-induced brain drain for consumer decision-making and consumer welfare.

Old Desires, New Media

w/ Diana I. Tamir

in The Psychology of Desire (Guilford Press, 2015)

Email for more information

"New media”—including televisions, computers, and smartphones—seem to offer simple solutions to complex social needs. With the change of a channel, we can connect with our “neighbor” Mr. Rogers or our “friends” on Friends; with the tap of a button, we can relive social events through Facebook photos or communicate with relationship partners on the other side of the earth. At times, these solutions may be real. At other times, however, our social minds may motivate behaviors that provide only the illusion of adaptive functioning. In this chapter, we provide an overview of how our widespread use of social media is encouraged by our social minds, and what it might mean for social outcomes. We explore the bases of our need for social connection, the brain’s reward system that motivates us to seek out social stimuli, and the mentalizing system that allows us to succeed in our social endeavors. We then turn to an analysis of how these components of our social minds contribute to our desire to find and create social connection through our screens. Finally, we offer some perspective on what this all might mean—whether our social minds are ruining or enhancing our relationships, both online and off.

the myth of harmless wrongs in moral cognition: automatic dyadic completion from sin to suffering

w/ Kurt Gray and Chelsea Schein

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (2014)

View Article Online

Download PDF

When something is wrong, someone is harmed. This hypothesis derives from the theory of dyadic morality, which suggests a moral cognitive template of wrongdoing agent and suffering patient (i.e., victim). This dyadic template means that victimless wrongs (e.g., masturbation) are psychologically incomplete, compelling the mind to perceive victims even when they are objectively absent. Five studies reveal that dyadic completion occurs automatically and implicitly: Ostensibly harmless wrongs are perceived to have victims (Study 1), activate concepts of harm (Studies 2 and 3), and increase perceptions of suffering (Studies 4 and 5). These results suggest that perceiving harm in immorality is intuitive and does not require effortful rationalization. This interpretation argues against both standard interpretations of moral dumbfounding and domain-specific theories of morality that assume the psychological existence of harmless wrongs. Dyadic completion also suggests that moral dilemmas in which wrongness (deontology) and harm (utilitarianism) conflict are unrepresentative of typical moral cognition.

Paying it Forward: generalized reciprocity and the limits of generosity

w/ Kurt Gray and Michael I. Norton

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (2014)

View Article Online

Download PDF

When people are the victims of greed or recipients of generosity, their first impulse is often to pay back that behavior in kind. What happens when people cannot reciprocate, but instead have the chance to be cruel or kind to someone entirely different—to pay it forward? In 5 experiments, participants received greedy, equal, or generous divisions of money or labor from an anonymous person and then divided additional resources with a new anonymous person. While equal treatment was paid forward in kind, greed was paid forward more than generosity. This asymmetry was driven by negative affect, such that a positive affect intervention disrupted the tendency to pay greed forward.

give what you get: capuchin monkey (cebus apella) and four-year-old children pay forward positive and negative outcomes to conspecifics

w/ Kristi Leimgruber, Jane Widness, Michael I. Norton, Kristina Olson, Kurt Gray, and Laurie Santos

PLOS One (2014)

View Article Online

Download PDF

The breadth of human generosity is unparalleled in the natural world, and much research has explored the mechanisms underlying and motivating human prosocial behavior. Recent work has focused on the spread of prosocial behavior within groups through paying-it-forward, a case of human prosociality in which a recipient of generosity pays a good deed forward to a third individual, rather than back to the original source of generosity. While research shows that human adults do indeed pay forward generosity, little is known about the origins of this behavior. Here, we show that both capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) and 4-year-old children pay forward positive and negative outcomes in an identical testing paradigm. These results suggest that a cognitively simple mechanism present early in phylogeny and ontogeny leads to paying forward positive, as well as negative, outcomes.

Supernormal: How the Internet is changing our memories and our minds

Psychological Inquiry (2013)

View Article Online

Download PDF

We are creatures of flesh and blood, living in a world of bits and bytes—a world shaped by the Internet. With the simple touch of a button or swipe of a finger, we can instantaneously access vast amounts of information (e.g., Ashton, 2009). A few more keystrokes, and we can interact with friends 10 time zones away (e.g., Thurlow, Lengel, & Tomic, 2004). Just a few more, and we may complete the transition to a digital life, transferring our identities from our physical bodies to online avatars (e.g., Bessiere, Seay, & Kiesler, 2007). When old cognitive tendencies and new technologies meet—when the world of flesh and blood collides with the world of bits and bytes—the Internet may act as a “supernormal stimulus,” hijacking preexisting cognitive tendencies and creating novel outcomes. The Internet is not changing the way we think, but it may be changing the outcomes of these ways of thinking—particularly in the domains of memory and information search.

Mind-Blanking: When the mind goes away

w/ Daniel M. Wegner

Frontiers in Psychology (2013)

View Article Online

Download PDF

Many times, people’s minds seem to go “somewhere else”—attention becomes disconnected from perception, and people’s minds wander to times and places removed from the current environment (e.g., Schooler et al., 2004). At other times, however, people’s minds may seem to go nowhere at all—they simply disappear. This mental state—mind-blanking—may represent an extreme decoupling of perception and attention, one in which attention fails to bring any stimuli into conscious awareness. In the present research, we outline the properties of mind-blanking, differentiating this mental state from other mental states in terms of phenomenological experience, behavioral outcomes, and underlying cognitive processes. Seven experiments suggest that when the mind seems to disappear, there are times when we have simply failed to monitor its whereabouts—and there are times when it is actually gone.

the harm-made mind: victimization augments perceptions of the mind of vegetative patients, robots, and the dead

w/ Andrew Olsen and Daniel M. Wegner

Psychological Science (2013)

View Article Online

Download PDF

People often think that something must have a mind to be part of a moral interaction. However, the present research suggests that minds do not create morality, but that morality creates minds. In four experiments, we find that observing intentional harm to an otherwise unconscious entity—a vegetative patient, a robot, or a corpse—leads to augmented attribution of mind to that entity. A fifth experiment reconciles these results with extant research on dehumanization by showing that victimizing conscious entities leads to reduced mind attribution, suggesting that the effects of victimization vary according to the victim’s preexisting mental status. People seem to make an intuitive cognitive error when unconscious entities are placed in harm’s way. They assume that if a moral harm occurs, then there must be someone there to experience that harm—a harm-made mind. These findings have implications for political policies concerning right-to-life issues.

Research: working papers